Poster #P25

Exploring the design space of metal-organic cages

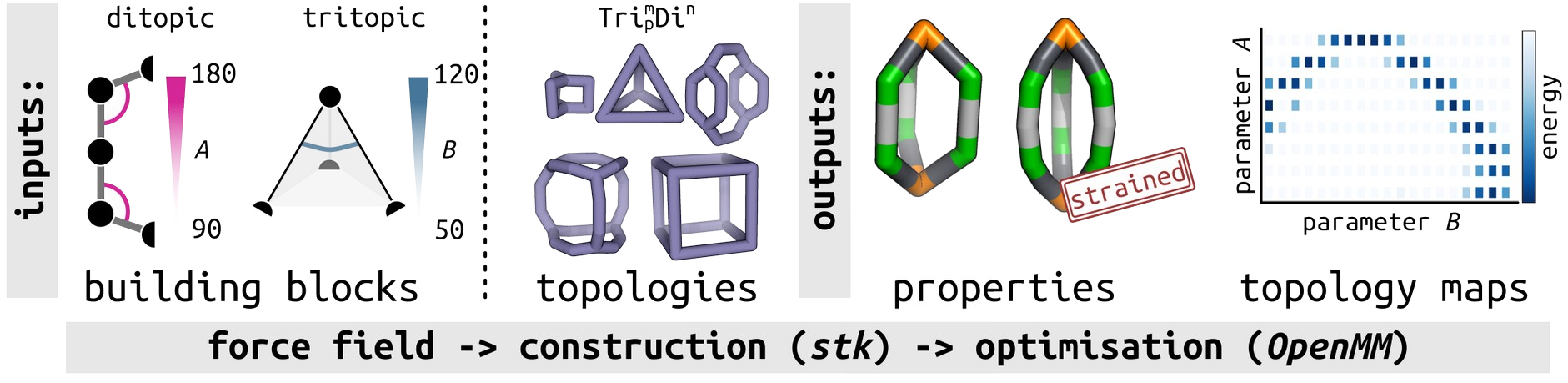

Cages are macrocyclic structures with an intrinsic internal cavity that support applications in separations, sensing and catalysis. These materials can be synthesised via self-assembly of organic or metal–organic building blocks. Their bottom-up synthesis and the diversity in building block chemistry allows for fine- tuning of their shape and properties towards a target property. However, it is not straightforward to predict the outcome of self-assembly, and, thus, the structures that are practically accessible during synthesis. Indeed, such a prediction becomes more difficult as problems related to the flexibility of the building blocks or increased combinatorial space lead to more challenging and more expensive computational studies.[1] Molecular models, and their coarse-graining into simplified representations, may be very useful to this end. We developed a toy model [Figure 1] approach for the exploration of the “stable” space of different cage structures based on their underlying topologies and building blocks.[2] In our first study, we show the relationship between a few fundamental geometric building block parameters and stable cage space. Our results capture, despite the simplifications of the model, known geometrical design rules in synthetic cage molecules and uncover the role of building block coordination number and flexibility on the stability of cage topologies. This leads to a large-scale and systematic exploration of design principles, generating data that we expect could be analysed through expandable approaches towards the rational design of self-assembled porous architectures.

Figure 1. Schematic of the inputs and outputs of the minimal cage model, from building blocks (defined by changing a few geometrical measures) and cage topologies, to cage structures (defined by strain energy) and maps of the building block parameters and their stability.

- R.-J. Li, A. Marcus, F. Fadaei-Tirani, K. Severin, Chem. Comm. 2021, 57, 10023-10026.

- A. Tarzia, E. H. Wolpert, K. E. Jelfs, G. M. Pavan., Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 12506-12517.

Andrew Tarzia

- Politecnico di Torino